What Happens When A Defamer Remain Anonymous?

by Alliff Benjamin Suhaimi & Angelene Cheah ~ 17 November 2020

Contributed by:

Alliff Benjamin Suhaimi (Partner)

Tel: 603-6201 5678 / Fax: 603-6203 5678

Email: ben@thomasphilip.com.my

Website: www.thomasphilip.com.my

Angelene Cheah (Pupil)

Defamation in the 21st century has taken many different forms. Information that used to be in traditional written form has now morphed onto various electronic platforms and medium. With new avenues of communication and disseminating information, comes new challenges. Most notably, people are using these new technologies and the internet to hide behind anonymity to evade any liability or punishment for anything they have posted or published.

Does this mean that there is no recourse for a potential victim whenever he or she is defamed by someone anonymous?

The High Court in the case of Stem Life Berhad v Mead Johnson Nutrition (Malaysia) Sdn Bhd & Anor [2013] MLJU 1582 illustrates how the courts in Malaysia have dealt with uncovering the identities of anonymous users on the internet.

In that case, the Plaintiff, Stem Life Berhad, is a public company in the business of offering stem cell banking services for expecting parents. The 1st Defendant, Mead Johnson also known as Bristol-Myers Squibb(M) Sdn Bhd, is the owner of a website known as www.meadjohsonasia.com and involved in the business of infant nutrition products (the “website”). The 2nd Defendant, Arachnid, is the web agency responsible for developing and maintaining the website. The website is a popular site for parents who are concerned about their children’s wellbeing and the website also provided a forum in which users are able to share their tips, views and opinions on parenting with other users.

The Plaintiff discovered defamatory postings concerning the Plaintiff’s business posted on the website by users known as “Stemlie” and “kakalily” (the “Users”). The Plaintiff lodged a police report and a complaint against the 1st Defendant with the Malaysian Communication and Multimedia Commission (“MCMC”). The Plaintiff via its solicitors demanded that the 1st Defendant provided full details the Users and remove the defamatory postings. The 1st Defendant contends that the posting were not defamatory, it was not responsible for the statements made and refused to provide full details of the Users. The defamatory posting was left on the website for more than two months.

Following the 1st Defendant’s refusal to provide details of the Users, the Plaintiff applied for a Pre-Action discovery by way of an application for a Norwich Pharmacal Order to compel the 1st Defendant to reveal the identity of the Users. The High Court in Stem life Bhd v Bristol-Myers Squibb (M) Sdn Bhd [2008] 6 CLJ 200 allowed the said application. The 1st Defendant complied with the Order but provided false information of the Users. Therefore, the Plaintiff could not commence proceedings against these two individuals.

However, the High Court in Stem Life Berhad v Mead Johnson Nutrition (Malaysia) Sdn Bhd & Anor held that the Plaintiff has successfully made out a case against the 1st Defendant on the basis that:-

- The 1st Defendant was the owner and editor of the website as stipulated in the terms and conditions of the website;

- The 1st Defendant has the autonomy and control over any publication on the website such as editing, regulating and removing postings on the forum; and

- The 1st Defendant did not monitor or control the publication which contains the defamatory statements concerning the Plaintiff.

As a result, the High Court allowed the Plaintiff’s claim for defamation against the 1st Defendant. The High Court held as follows:-

“Where a libel is made on the internet, an action may lie against amongst others, the author, website owner, website editor, internet service provider, content developer, website administrator and so forth. This unfortunately is not clear law under the Malaysian jurisprudence as it is still a developing area of the law.

Under the Defamation Act 1957, there are no specific provisions governing liability for cyber libel, hence reference is to be made to the common law.”

“In Godrey v Demon Internet Ltd [1999] 4 All ER 342, Morland J was dealing with defamation over the internet and stated as follows:

At common law, liability for the publication of defamatory material was strict. There was still publication even if the publisher was ignorant of the defamatory material within the document. Once publication was established the publisher was guilty of publishing the libel unless he could establish, and the onus was upon him, that he was an innocent disseminator.”

The introduction of Section 114A of the Evidence Act 1950 is the Malaysian’s legislature response to address, amongst others, the issue of anonymity on the internet to ensure users do not exploit anonymity that the internet can provide to escape the consequences of their actions. Section 114A covers liability such as owners of websites to network service providers which are as follows:-

“Section 114A. Presumption of fact in publication

1. A person whose name, photograph or pseudonym appears on any publication depicting himself as the owner, host, administrator, editor or sub-editor, or who in any manner facilities to publish or re-publish the publication is presumed to have published or re-published the contents of the publication unless the contrary is proved.

2. A person who is registered with a network service provider as- a subscriber of a network service on which any publication originates from is presumed to be the person who published or re-published the publication unless the contrary is proved.

3. Any person who has in this custody or control any computer on which any publication originates from is presumed to have published or re-published the content of the publication unless the contrary is proved.

4. For the purpose of this section-

- "network service" and "network service provider" have the meaning assigned to them in section 6 of the Communications and Multimedia Act 1998 [Act 588]; and

- "publication" means a statement or a representation, whether in written, printed, pictorial, film graphical, acoustic or other form displayed on the screen of a computer.”

In light of the Section 114A provision, website providers or owners of social media platforms plays a vital role in uncovering anonymity of a user who has indulge in defaming another user on their website/platform. Therefore, more often than not, pre-action discovery orders are made against website or social media providers/owners to obtain information to expose the anonymous defamer.

Although this can be a cumbersome and long process as seen in the case of Tong Seak Kan & Anor v Loke Ah Kin & Anor [2014] 6 CLJ 904. The facts of the case are as such, the first plaintiff was a prominent business man and his wife, the second plaintiff sued the first defendant for posting defamatory statements on two blogs. The first defendant denied that the two blogs belonged to him, he had nothing to do with the publications and that he does not even know the plaintiffs. To find out who the culprits behind the two blogs were, the plaintiffs filed a John Doe action against Google Inc in the Superior Court in California USA.

In compliance with the court order, Google traced the two blogs to internet protocol (IP) addresses which revealed that the IP addresses were within the blocks allocated to Telekom Malaysia. The plaintiffs subsequently commenced proceedings against Telekom Malaysia as the network providers for an order to compel them to disclose information on the IP address of the two blogs. Pursuant to the said order, Telekom Malaysia confirmed that the IP address belonged to the 1st Defendant. Based on the confirmation by the service providers that the 1st Defendant was the owner of the two blogs, the presumption of Section 114A of the Evidence Act 1950 kicks in. However, the 1st Defendant failed to provide any evidence to prove that he was not the person who wrote the defamatory statements.

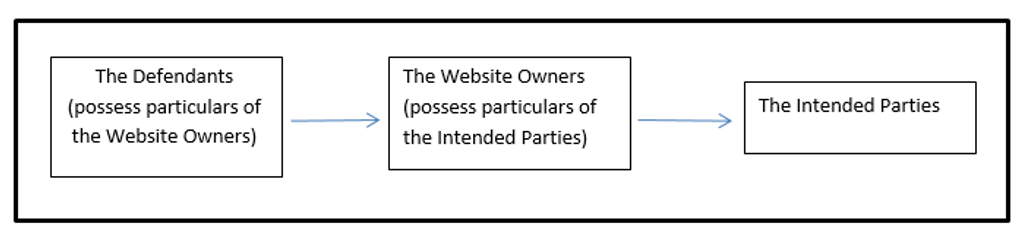

In another case, the High Court in Kopitiam Asia Pacific Sdn Bhd v Modern Outlook Sdn Bhd & Ors [2018] MLJU 1450 allowed an application for pre-action discovery order against the Defendants who were connected to the website owners where the defamatory article against the Plaintiff was posted as explained below. It must be noted that a pre-action discovery which was previously known as a Norwich Pharmacal Order has now been given statutory effect by way of Order 24 Rule 7A of the Rules of Court 2012.

The Plaintiff being a franchise owner of a café outlet named “OLD TOWN WHITE COFFEE” discovered an offensive and defamatory article pertaining to its ownership and quality of products circulating on websites connected to the Defendants. The Plaintiff intended to file an action against the author of the said defamatory article (the “Intended Parties”) who posted the article on a website named https://thecoverage.my.

However, the Plaintiff does not possess the particulars and information of the Intended Parties but contends that the Defendants have such information. Although the Plaintiff wrongly stated that one of the 3rd Defendant was the administrator, the Plaintiff’s search found that the director of the 3rd Defendant is the contact person and was also the person who registered the domain name “the.coverage.my”. The High Court found that this discovery order was necessary for the Plaintiff and for the purposes of filing an action against the Intended Parties. As such, the Defendants were compelled to reveal the identity of the Intended Parties.

In another High Court case of Nik Elin Zurina binit Nik Abdul Rashid v Mesra.net Sdn Bhd (Kuala Lumpur High Court Suit No. WA-24NCvC-179-02/2018) (Unreported), the plaintiff sought a pre-action discovery order against the Defendant who was the sole administrator for web addresses that end with “.my” in Malaysia. The plaintiff discovered defamatory articles against her on the website of “Menara.my”. The Defendant would have information of the owner of the domain name as the Defendant has assisted in the registration of the domain name “Menara.my”. The High Court allowed the plaintiff’s application and the defendant had to provide the identity of the owner of the website.

In this age of the internet the old adage that the pen is mightier than the sword can no longer hold true. It is the swashbuckling keyboard that has taken over.

Not all hope is lost whenever a defamer hides behind anonymity to evade their liabilities of what was said on the internet, there are methods (albeit troublesome) in uncovering and revealing anonymous defamers and bringing an action against them.

Furthermore, the introduction of Section 114A of the Evidence Act 1950 shows that the Malaysian legislation and the courts alike are vigilant in tackling anonymity on the internet as it is still a developing area of law.