The CVA Scheme and How it Compares to Other Corporate Rescue Mechanisms

by Lavinia Kumaraendran & Sean Tan Yang Wei ~ 18 April 2020

Corporate, Insolvency and Restructuring Team

Lavinia Kumaraendran

Email: lkk@thomasphilip.com.my

Sean Tan Yang Wei

Email: tyw@thomasphilip.com.my

Following the recommendations of the Corporate Law Reform Committee (“the CLRC”), new mechanisms were introduced to facilitate the rehabilitation and restructuring of companies facing financial difficulties. This was meant to reduce the number of companies being wound up, particularly when the businesses in question are capable of being turned around.[1]

Thus, the Companies Act 2016 introduced the Corporate Voluntary Arrangement as one of the new schemes to rescue businesses in financial distress.

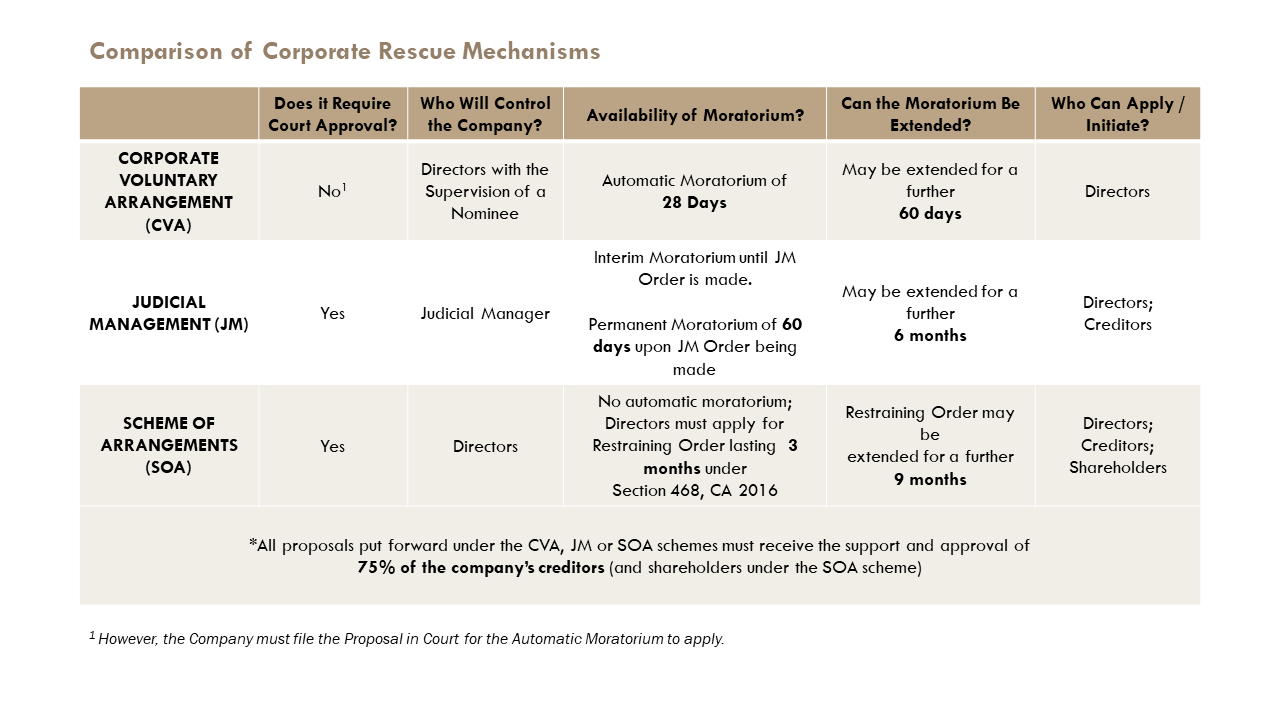

This article aims to give the reader an overview as to the features of the Corporate Voluntary Arrangement mechanism and its comparison against the Judicial Management[2] and Arrangement and Reconstruction[3] mechanisms to help companies consider the options best suited to them in the event that such a scheme is needed to rescue their businesses.

CORPORATE VOLUNTARY ARRANGEMENT

Section 397 of the Companies Act 2016

Essentially, a Corporate Voluntary Arrangement (“CVA”) is an agreement made between the company and its creditors to reach a compromise on the whole or part of the company’s debts and its repayment.

Firstly, it must be noted that the CVA mechanism is not available to

- public companies,

- companies regulated by laws enforced by the Central Bank of Malaysia, companies subject to the Capital Markets and Services Act 2007; and

- companies which have created charges over its property or part of its undertaking.[4]

Thus, the CVA is only applicable to private companies which have not created charges over its property (i.e. with no secured debt). I will explain below how that is not feasible as a rescue mechanism.

The CVA can be proposed by the directors of a company (which is not being wound up or under judicial management).[5] A CVA can also be proposed by a liquidator or a judicial manager in cases where the company is being wound up or has been placed under judicial management.[6]

General Procedure of a CVA

The directors of the company will need to prepare and put forward the terms of the proposed arrangement (“the Proposal”) and appoint a Nominee to work with. The Nominee must be an insolvency practitioner and is responsible for supervising the implementation of the proposal.

Once the Nominee is appointed, the Proposal is submitted to the Nominee for review and approval. If the Nominee is of the opinion that the Proposal is viable, then the documents setting out the terms of the CVA can be filed in Court.[7]

Upon the filing of the documents in Court, an automatic moratorium applies and remains in force for 28 days. This moratorium is intended to protect the company from legal actions taken against it by its creditors while the Proposal is being considered. The moratorium can be extended for not more than 60 days (with the approval of 75% of the company’s creditors, nominee and members of the company).

After the Proposal is approved by the Nominee, the Nominee will summon a meeting of shareholders and a meeting of creditors to consider and approve the Proposal (which must be called within 28 days from filing in Court).

The Proposal must garner the approval of a majority of shareholders and 75% of the creditors of the company. Once it is approved, the Proposal takes effect and is binding on all creditors of the company. [8]

Key Features and Advantages

1. Appointment of a Nominee

The CVA scheme requires the Company to appoint a Nominee to supervise the proposal’s implementation. The Nominee is also responsible for providing an opinion on the viability of the Proposal put forward by the directors and must state that it has a reasonable prospect of being approved and implemented.

|

…the directors of the company retain their powers of the day-to-day management of the company. |

During the period of the moratorium, the Nominee has a duty of monitoring the affairs of the company to ensure that the company can sustain its business before the Proposal is approved.

After the Proposal is approved, the Nominee’s main function is one of oversight and supervision. The Nominee is required to make the necessary distribution or payments to the company’s creditors in accordance with the terms of the Proposal. However, at all times before and after the Proposal is approved, the directors of the company retain their powers over the day-to-day management of the company.

2. Simple and Straightforward

The CVA mechanism is also perhaps the simplest of the 3 corporate rescue mechanisms available under the Companies Act 2016 as it does not require the plan or agreement to be approved by Court. The arrangement only requires the approval of 75% in value of the company’s creditors and a simple majority of the company’s shareholders.

Aside from the requirements to file the documents outlining the terms of the Proposal to Court (for the moratorium to take effect), no further Court order is required for the Proposal to be implemented. In this regard, it is a cost-effective mechanism for companies to restructure its debts with its creditors as the legal costs involved would be significantly lower.

3. Availability of a Moratorium

As outlined above, an automatic moratorium applies to protect the company from legal actions once the Proposal has been filed in Court. This moratorium or freezing of legal proceedings against the company would allow the company to be protected from having to defend multiple legal proceedings initiated by disgruntled creditors seeking to recover their debts from the company. As the legal and execution proceedings can be expensive to fend off, the protection offered by the moratorium would mean that the company would not have to expend precious resources on legal fees to oppose these legal proceedings and will instead be able to channel these resources into sustaining the business of the company while the Proposal is being approved.

Based on its key features, the CVA mechanism is an attractive and practical option for many smaller businesses facing financial difficulties. However, it is worth noting the major differences between the CVA mechanism and other available corporate rescue options available to companies.

CVA v JUDICIAL MANAGEMENT – KEY DIFFERENCES

Both the CVA and Judicial Management schemes are aimed towards ensuring that a restructuring plan is put in place to rescue the business of the company. Both schemes also require any restructuring proposal to be approved by 75% of the company’s creditors. However, there are several key differences which exist between these schemes.

Firstly, the Judicial Management scheme will be more costly to implement as it involves an application to be made to Court for an order to appoint a judicial manager in the target company. This application can be made either by the directors of the company or any creditor of the company. Once an application for a judicial management order is made, an automatic moratorium applies and remains in force until the judicial management application is disposed of. If the application is heard and allowed by the Court, then the moratorium will be made permanent and will remain in force for the entire duration of the judicial management.

Secondly, the Judicial Management scheme is much more invasive as it involves the Court appointing an insolvency practitioner to directly manage the affairs of the company. Unlike the CVA scheme where the directors remain in control of the company’s affairs, all management powers of the company are taken away from the company’s directors and are placed in the hands of the court-appointed judicial manager. Once appointed, the judicial manager is tasked with running the company, protecting its assets, and coming up with a restructuring proposal for the company. If the restructuring proposal is approved, the judicial manager will then be tasked with the responsibility of implementing the proposal. The judicial manager is given a duration of 6 months to prepare and implement a proposal, which can be extended by a further 6 months upon application to Court.

CVA v SCHEME OF ARRANGEMENTS[9]

The arrangement or reconstruction provisions (commonly referred to as the “Scheme of Arrangements”) under Section 366 of the Companies Act is the classic corporate reconstruction provision in Malaysia and has been used extensively in the past for companies as a means to restructure its debts with its creditors. The Scheme of Arrangements mechanism can also be used for restructuring the corporate structure of the company, such as for the restructuring or reduction of share capital or the replacement of holding companies.

Much like the CVA mechanism, the affairs of the company remain under the management of its directors under the Scheme of Arrangements. The Scheme of Arrangements also requires that the proposal be approved by 75% in value of the company’s creditors and a majority of its shareholders[10].

However, the proposal under the Scheme of Arrangements mechanism must also be approved by the Court and involves various stages of Court proceedings prior to its implementation. Thus, provision must be made by the company to pay for the legal costs involved in putting forward a proposal under this scheme.

More importantly, however, is the fact that there is no automatic moratorium available under the Scheme of Arrangements mechanism, unlike the CVA and Judicial Management Provisions. Instead, the company must apply for a restraining order under Section 368 of the Companies Act 2016 in order to obtain protection for the company against legal and execution proceedings. Without the benefit of an automatic moratorium and a restraining order, a company seeking to restructure its debts under the Scheme of Arrangement mechanism will be significantly more exposed to legal and execution proceedings throughout the process.

WHEN SHOULD THE CVA BE CONSIDERED?

The limitation placed by statute against companies with charges means that many companies are technically precluded from considering the CVA mechanism as many companies tend to create charges over their assets as security for financing from financial institutions. So companies in this day and age would have obtained some form of financing with security, however small. With that in place, CVA will not operate to be a rescue mechanism available for it and as such used in very limited circumstances.

Having said that, the CVA should largely be considered by smaller private companies which are facing financial difficulties. The simple and straightforward mechanism is an attractive option since it is cost-effective and takes significantly less time than the Judicial Management and Scheme of Arrangement mechanisms. The availability of an automatic moratorium also means that companies have a simple way of obtaining protection against legal and execution proceedings while it attempts to rescue its business.

Moving forward, for many businesses which may be facing financial difficulties as a result of the unfortunate and unprecedented times, reform ought to be lent towards these rescue mechanisms. Some of which must be seen to relax these stringent rules and allow for more flexibility for companies to adopt these rescue mechanisms. Ultimately, whatever the proposal maybe that is suggested must be one that is reasonable and likely to be implemented. A viable and workable proposal is the only way companies can convince its creditors and pull through these challenging times.

[1] Review of the Companies Act 1965 – Final Report by the Corporate Law Reform Commission

[2] Section 406, CA 2016

[3] Section 366, CA 2016

[4] Section 395, CA 2016

[5] Section 396(1), CA 2016

[6] Section 396(3), CA 2016

[7] Sections 397(2) and 398(1), CA 2016

[8] Section 400(2) and (3), CA 2016

[9] Section 366, CA 2016

[10] Note that the requirement of the approval of creditors is only relevant in schemes which affect the rights of creditors. Where a scheme does not affect the rights of creditors, approval will only require the majority support of the company’s shareholders.