The Challenges of WhatsApp Evidence at Trial

by Nicholas Wong Kwang Tee ~ 21 April 2020

Contributed by:

Nicholas Wong Kwang Tee (Associate)

Tel: 603-6201 5678 / Fax: 603-6203 5678

Email: wkt@thomasphilip.com.my

Website: www.thomasphilip.com.my

As cross-platform message services like WhatsApp become more ubiquitous, more and more of these messages are finding their way into the Courts as evidence at trial. However, they also present new and unique challenges for lawyers to navigate.

The law

There is, of course, no issue as to admissibility if both parties agree to put the WhatsApp evidence in question in Part B – that is if there is no dispute as to the authenticity of the messages.

What if your opponent does dispute the authenticity of your WhatsApp evidence – that is, what if they insist on putting it in Part C? This was exactly what the High Court case of Mok Yii Chek v Sovo Sdn Bhd & Ors [2015] 1 LNS 448 considered. The parties in that case had actually agreed the WhatsApp messages were Part B evidence; however, the Court helpfully went on to consider how such evidence could be adduced otherwise.

Other than the need to overcome the usual evidentiary hurdles of evidence (that it concerns the existence or non-existence of a fact; that it is relevant; whether or not it is hearsay), the Court further held that print-outs of WhatsApp messages were ‘documents’, in this case, produced by a computer, falling within the broad meaning of section 3 of the Evidence Act, 1950. Such ‘documents’ therefore constituted primary evidence which could be adduced under section 64 of the 1950 Act.

Section 90A provides specifically for the admissibility of documents produced by computers, most notably by requiring that they were ‘produced by the computer in the course of its ordinary use’ (section 90A(1) of the 1950 Act). Here, the Court of Appeal in Gnanasegaran Pararajasingam v PP [1997] 4 CLJ 6 set out two ways by which this could be done: firstly, by giving oral evidence that it was so produced, or secondly, by producing a certificate under section 90A(2) of the 1950 Act. This was later followed by the Federal Court in Ahmad Najib bin Aris v Public Prosecutor [2009] 2 MLJ 613 as well as the High Court in the aforementioned Mok Yii Chek case.

(It should, however, be noted that neither Gnanasegaran nor Ahmad Najib dealt with WhatsApp evidence specifically)

Practical considerations

The long and short of it is that, whether by way of oral evidence or a section 90A(2) certificate, WhatsApp messages may be adduced in Court notwithstanding initial disputes as to their authenticity. However, they remain open to attack on their authenticity as well as on the issue of the weight to be given to them as evidence. This is where unique challenges arise.

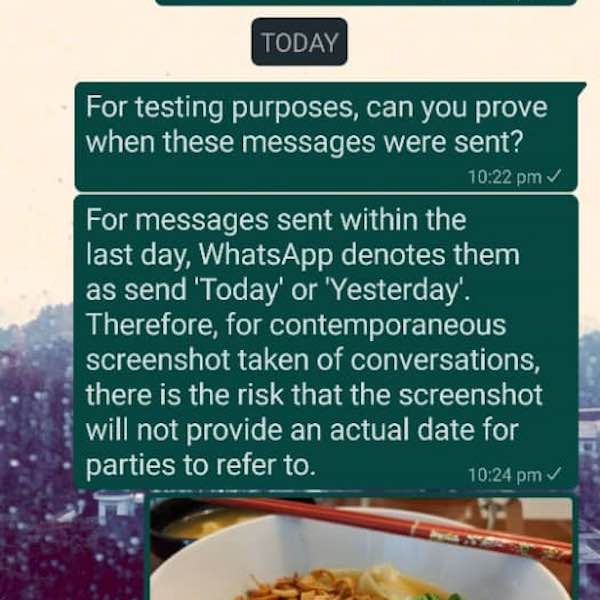

Screenshots of WhatsApp conversations. The format in which the WhatsApp conversation is produced matters. Clients often supply screenshots of their WhatsApp conversations, but depending on how and when they are taken, problems may occur. Here is an example of one such screenshot, mocked up for illustrative purposes:

Such a screenshot would be open to challenge on the basis that they do not indicate the date of the alleged text messages. As you can see from the screenshot, messages sent in the past are date-stamped (‘2 April 2020’) but messages sent on the same day are only marked ‘Today’. Likewise, messages sent the day before are marked ‘Yesterday’. Neither is the date displayed next to the phone’s clock in the notification bar (although depending on the model and make of your client’s phone, you may have better luck).

Worse still is that the ‘Today’ label only appears at the top of the messages sent on the day – if your conversation runs longer than that, no date-stamp or label will appear at all.

Fortunately, the date-stamp hovers over the conversation for messages sent 2 days before. This is, therefore, more of a problem for screenshots taken contemporaneously. Practically, what this means is that there is less issue with your client taking screenshots of old conversations – but they should be warned of these problems if they are in the habit of taking screenshots as and when conversations happen.

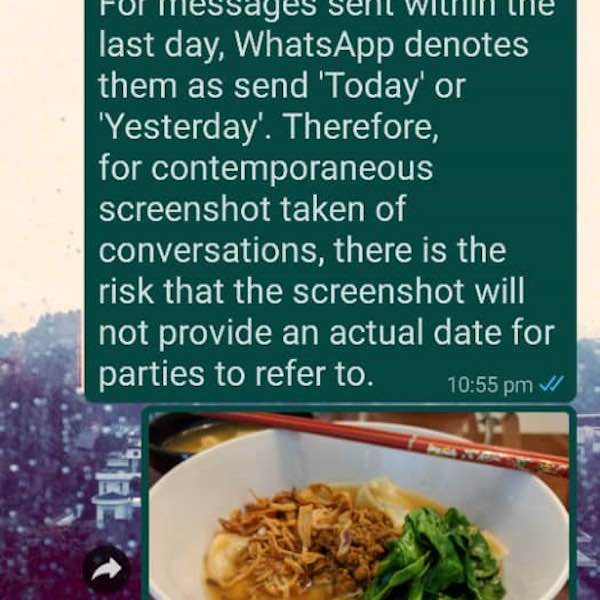

Exported WhatsApp Chats. Is there a better way? Your clients may also export their WhatsApp conversations using the app’s settings (go to the Settings/Chats/Chat history/Export chat – then select the conversation to export). This will create a plain text file (a .txt file) which you can save to your device or share via another app (to email to yourself, for example).

When you open such a text file, it will appear as follows:

12/04/2020, 10:55 pm - Nicholas Wong: For testing purposes, can you prove when these messages were sent?

12/04/2020, 10:55 pm - Nicholas Wong: For messages sent within the last day, WhatsApp denotes them as send 'Today' or 'Yesterday'. Therefore, for contemporaneous screenshot taken of conversations, there is the risk that the screenshot will not provide an actual date for parties to refer to.

12/04/2020, 10:55 pm - Nicholas Wong: <Media omitted>

12/04/2020, 10:56 pm - Saksi #01: hello, thank you

The messages are all date- and time-stamped, which is much more helpful than the previous screenshots. Exporting chats is, therefore, a more comprehensive, and arguably neater way of introducing WhatsApp conversations into evidence – particularly if the conversation to be referred to is a lengthy one.

Note that if you access a WhatsApp conversation via WhatsApp Web on your laptop or desktop, you can also quickly create a similar transcript-like output of a conversation by manually copying the messages you are interested in and pasting them in a text file or a document.

However, any media in the conversation - such as photos and videos - are necessarily omitted (as it’s only a text file). This may present another challenge to you if the presence of the media in the conversation is itself relevant to the evidence you are looking to present.

WhatsApp and tampering. Unfortunately, WhatsApp’s ultimate pitfall is that it is relatively easy to manipulate and even fabricate conversations. As WhatsApp’s export chat function only creates editable .txt files, these can be opened and altered by anybody. While WhatsApp does have a backup function, wherein backups of your messages are saved in Google Drive, these do not appear to be accessible by the user (it is the app which accesses it directly to restore your messages) – so they are of no use otherwise.

Another problem is that neither the screenshot nor the transcript above can prove the identity of the other party to the conversation. They only display the name of the other side as you have saved them in your contact book.

It is therefore easy for anyone with ulterior motives to fake a WhatsApp conversation by using two different phone numbers to fabricate both sides of a conversation. Depending on the facts of the case (how long ago the conversation allegedly took place, whether there is any corroborating evidence or lack thereof), this may prove convincing to a judge looking for doubts in the evidence.

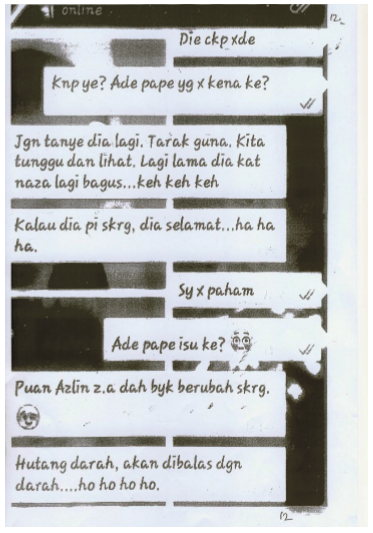

This is in fact what happened in the Industrial Court case of Mohamad Azhar bin Abdul Halim v Naza Motor Trading Sdn Bhd, case no. 4(2)(4)/4-241/15, where the Court found the following screenshot of a WhatsApp conversation lacking and ultimately unreliable. Like our sample screenshot above, this screenshot lacks a date-stamp. Unlike our sample, this one does not even indicate the other party to the conversation. A demonstration was conducted in Court to illustrate how a WhatsApp conversation could be fabricated, which also factored into the Court’s finding that the conversation was suspect.

How might these concerns be dealt with at trial? Firstly, the safest course of action would be to produce the original WhatsApp messages as they appear on the witness’ phone. Of course, this will not always be feasible as old messages are lost and old phones are discarded. This was again another issue in Mohamad Azhar.

Secondly, parties may choose to rely on a combination of both screenshots of the messages in question as well as the exported text versions of the conversation, for completeness.

Thirdly, parties should make an effort to obtain corroboration of the evidence in the WhatsApp conversation. This may include producing a subpoenaing as a witness the other party to the conversation and having them produce their end of the WhatsApp conversation as corroboration. Adducing other relevant and contemporaneous evidence of the matters referred to such WhatsApp conversations is, of course, trite and good practice.

Ultimately, what is clear is that WhatsApp evidence should, ideally, not form the linchpin of any party’s case in Court, given the various ways in which such evidence can be challenged.