Defamation: Restraining False Publications Online

by Phoebe Loi Yean Wei ~ 29 April 2021

Under Article 10 of our Federal Constitution, everyone has the right to freedom of speech. There is no doubt that this right is important and must be protected for obvious reasons. However, it must be balanced against the right of a person to not be defamed. This is the primary purpose of defamation law, which is essentially a balancing of two competing rights – the right to freedom of speech and the right to reputation.

With the advent of technology, breaking news can reach anyone with an internet connection in a matter of seconds. At the click of a share button, a blogger or social media user’s post can easily go viral on the internet and reach thousands of people in a short period of time. This is especially the case when sensational or catchy headlines are used to quickly grab the attention of online readers. Clearly, the damage which can result from this is likely to be serious and irreparable. The longer these posts remain online, the greater the damage.

When one is faced with such a situation, the usual course of action that is often taken starts with the issuance of a letter of demand, followed by legal proceedings. However, there will be circumstances where the contents of the publication are so damaging that it cannot be allowed to remain published and therefore urgent action is required to restrain such publications.

Interim Injunction in Pending Legal Proceedings for Defamation

Where there is an urgent need to restrain or remove false publications online, the suitable remedy here is to apply to the court for an interim injunction against the defamer until the legal suit has been fully disposed of.

An interim injunction is a temporary and discretionary remedy granted by the courts for the purpose of compelling or forbidding a specified party from doing a certain act. Injunctions can be classified into two natures – prohibitory and mandatory. Prohibitory injunctions restrain or prevent an act from being done, whereas mandatory injunctions compel or force the performance of a certain act.

Generally speaking, a person who has been defamed can apply to the court for an interim injunction to either:-

1. restrain the defamer from publishing defamatory statements; or

2. compel the defamer to delete or remove the publication from the internet.

Even if there is only a threat of publication, the court may still grant a quia timet order to restrain the intended publication if it can be shown that a statement defamatory of the plaintiff is about to be published (explained further below). This is another type of injunction where a wrongful act is anticipated.

If the court allows the application, the injunction will remain in force until the legal proceedings is disposed of. However, it must be noted that courts are generally reluctant to grant interim injunctions in defamation or libel cases, as the nature of the remedy interferes with a person’s right to freedom of speech.

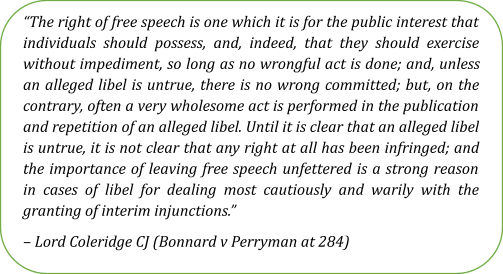

In the case of Bonnard v Perryman [1891] 2 Ch 269, the Court of Appeal emphasised that interim injunction for defamation cases should only be granted in the “clearest of cases” where the alleged libel is untrue:-

The above principle laid down by the English courts has been adopted in Malaysia, where our courts have agreed that interim injunctions will only be granted in defamation cases where the words, statements or publications complained of are clearly untrue or the defences which the defamer has relied on will fail (see: The New Straits Times Press (M) Bhd v Air Asia Bhd [1987] 1 MLJ 36).

The requirements which must be satisfied before a court will grant an interim injunction in defamation cases was set out in the case of Ngoi Thiam Woh v CTOS Sdn Bhd & 2 Ors [2001] 4 MLJ 510 as follows:-

1. the statement is unarguably defamatory;

2. there are no grounds for concluding that the statement may be true;

3. there is no other defence which might succeed; and

4. there is evidence of an intention to repeat or publish the defamatory statement.

The burden of proving all the above requirements lies on the plaintiff and not the defendant.

The Statement is Unarguably Defamatory

To establish that the statement complained of is unarguably defamatory, it must be shown that there are defamatory meanings arising from the words. The threshold for this was established in the oft-cited case of Syed Husin Ali v Sharikat Penchetakan Utusan Melayu Berhad & Anor [1973] 2 MLJ 56.

In gist, a statement is defamatory if it has the tendency to cause adverse opinions to be formed against the plaintiff or it would lower the plaintiff in the estimation of right-thinking members of society. For example, if Person A publishes a statement saying that Person B used the funds of a company for his own personal interest, the potential defamatory meanings which can arise from this statement is as follows:-

1. Person B is dishonest;

2. Person B has committed a criminal breach of trust; and

3. There has been serious misconduct by Person B.

No Grounds for Concluding that Offending Publications May Be True

Under this requirement, a plaintiff needs to show that there is strong prima facie evidence that the statement complained of is untrue. This means that the court will look at the evidence adduced in the exhibits and decide whether these evidences, on a prima facie basis, show that the statement complained of is clearly untrue.

The court will also look at whether the defendant has adduced any evidence that sufficiently shows that the statements complained of may in fact be true.

No Other Defence Which Might Succeed

The court will also consider the defences raised by the defendant and whether any of them might succeed. If there are, the court is unlikely to grant the interim injunction. One such example is where the defendant has raised the defence of qualified privilege.

Qualified privilege is a defence that applies in situations where the words have been published:

1. by a person ‘who has an interest or a duty, legal, social, or moral, to publish the words to the person(s) to whom they were published’; and

2. the person(s) to whom the words were published ‘had a corresponding interest or duty to receive them’.

In the case of Harakas v Baltic Mercantile and Shipping Exchange Ltd [1982] 1 WLR 958, it was held that where the occasion under which the statement was published is protected by qualified privilege, the courts should not grant an injunction that prevents a person from exercising his rights under such privilege unless it can be shown that the statements have been made maliciously.

Another example is where the defendant has relied on the defence of justification. This means that the defendant is arguing that the statement complained of is true. As explained earlier, if there are evidence to suggest the statement may be true and as such this defence might succeed, the court is unlikely to grant the interim injunction as well.

Evidence of an Intention to Repeat or Publish the Defamatory Statement

The final requirement that needs to be met is that there must be evidence of an intention by the defendant / defamer to repeat or publish the statement complained of. As mentioned earlier, the court has the ability to grant what is known as a ‘quia timet injunction’. This type of injunction comes into play where it is anticipated that defamatory statements are about to be published and there are evidence showing this. An example of this can be seen from the case of Petroliam Nasional Bhd & Ors v Khoo Nee Kiong [2003] 4 MLJ 216.

In the case of Petroliam Nasional, the defendant had issued an email to the plaintiffs containing statements which are defamatory and clearly referred to the plaintiffs. No defences were raised by the defendant in this case save for a bare denial. The court found that there was reason to believe that there would be an intended publication or further publication of the impugned statements, or the threat of it, which warrants the grant of the order. The plaintiffs had shown the court that the defendant repeated the impugned statements on numerous occasions and threatened to republish the said statements worldwide.

In another case, Synergistic Duo Sdn Bhd v Lai Mei Juan [2017] 9 MLJ 697, the court granted an interim injunction against the defendant to restrain her from publishing two defamatory publications until the hearing and final disposal of the suit. The defendant, in this case, had published two postings on her Facebook account regarding the plaintiff’s restaurant which went viral.

Prior to the substantive hearing of the injunction application, the court had granted an ad interim injunction against the defendant which restrained her from publishing the defamatory statements until the said hearing. However, the defendant refused to comply with the ad interim injunction and continued to publish the defamatory statements. It was held by the court that the defendant’s failure or refusal to comply with the ad interim injunction is evidence that she will continue to publish the defamatory statements. The continued publication would also result in further damage to the plaintiff’s reputation and goodwill as the potential re-publication of the postings to potentially an unlimited number of internet users would irreparably harm the plaintiff’s reputation

Conclusion

From the above, it is clear that courts are always slow to grant interim injunctions in defamation cases as it fetters with a person’s right to freedom of speech.

Another reason for this is due to the fact that the granting of an interim injunction may result in the determination of the entire suit in view of the factors that the court has to consider before deciding whether the injunction should be granted. Therefore, the general principle here is that courts should not grant an interim injunction unless the above requirements have been clearly met.

The threshold to obtain interim injunction cases may be high, but it is not impossible.

This is clear from the fact that Malaysian courts have, in the past, granted interim injunctions in defamation cases. The mode of publication will be an important consideration for the courts when deciding whether to grant the injunction.

It has been said that the internet is a “borderless unrestricted environment” where the statements could be published to an unlimited number of internet users including local and foreign industry players and corporations. As such, if the defamatory statements are published online, it would likely result in immediate, irreparable injury and damage to the person or company who has been defamed. In such circumstances, monetary compensation is unlikely to be adequate and the court would be more inclined towards granting the injunction sought.